Over the past month, I have been reviewing the garden seed catalogs that we have requested for 2026. In total, I looked at and scored nine catalogs. If you missed them, links for each review are located below, and for a refresher, here is the criteria I used to score them:

- Number of pages – 1 point per page over 100 pages; minus-1 point per page under 100 pages.

- New varieties – 1/2 (.50) point for each new variety for 2026.

- Total number of seeds – 1/4 (.25) point per seed.

- Selection of “Specialty Seeds” – By “Specialty Seeds,” I mean any specially designated seeds that are separated from the other seeds. Examples are All-American Selections, Italian Gourmet, and Indigenous Royalties. – 1 point will be awarded for each specialty category.

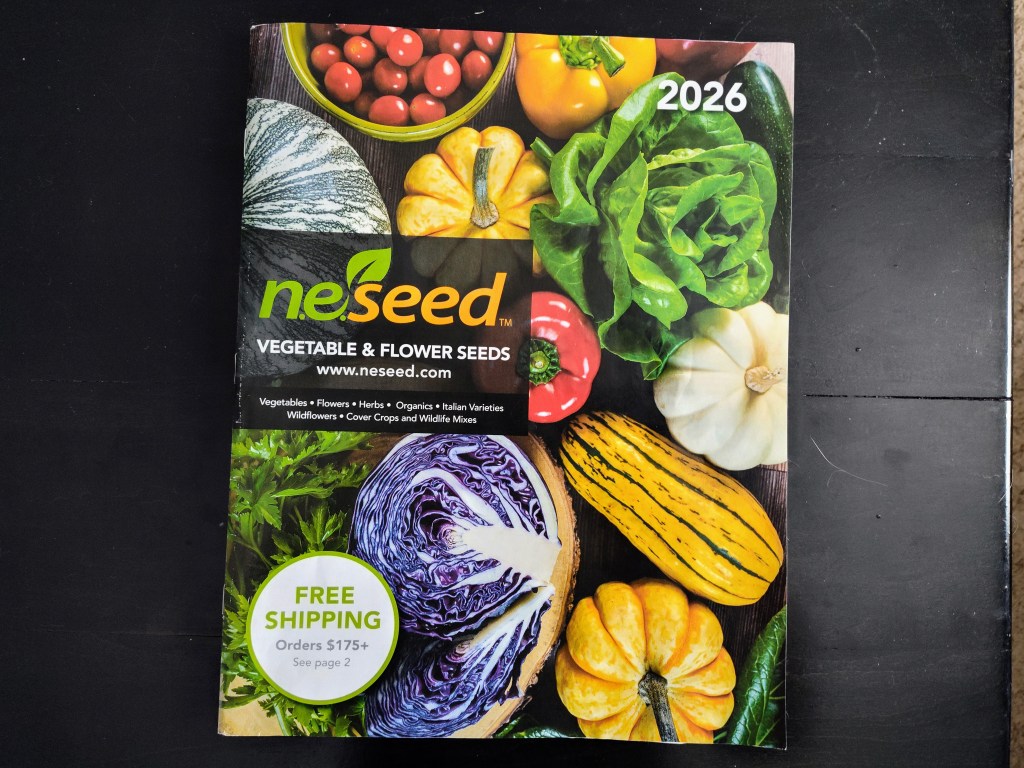

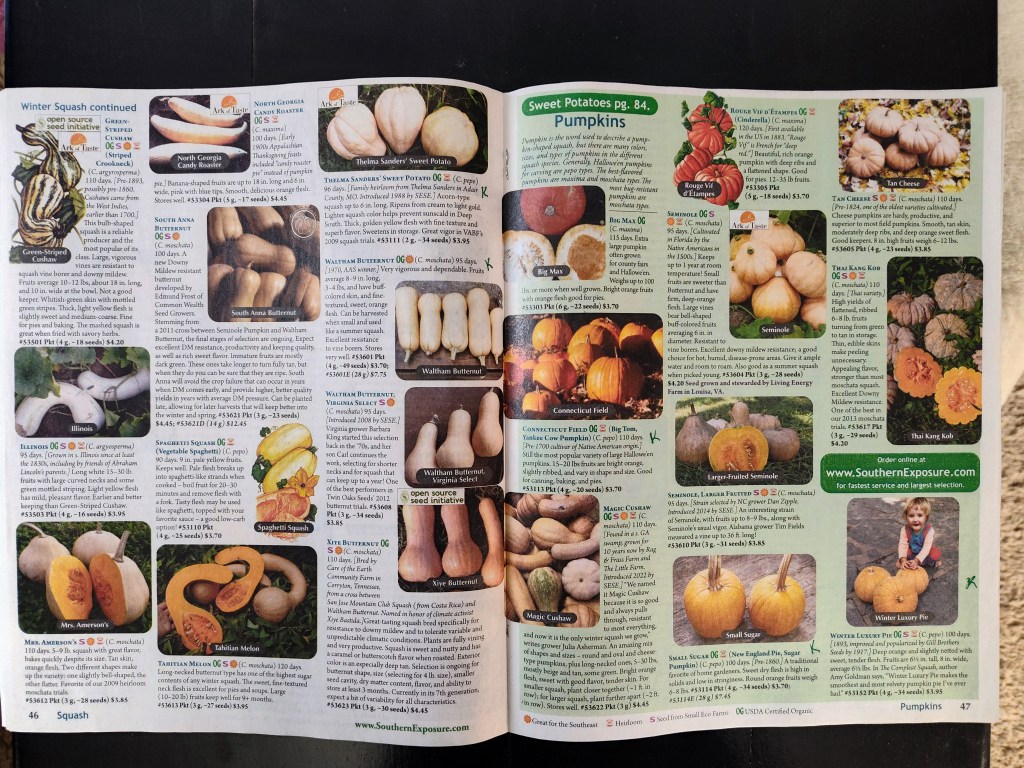

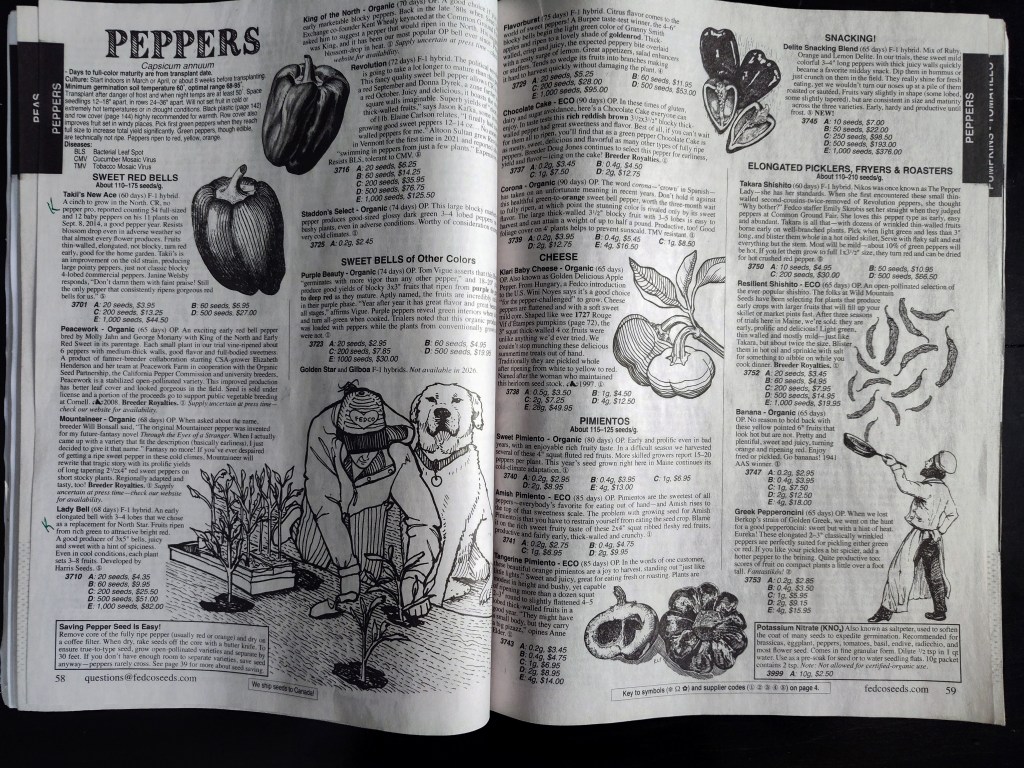

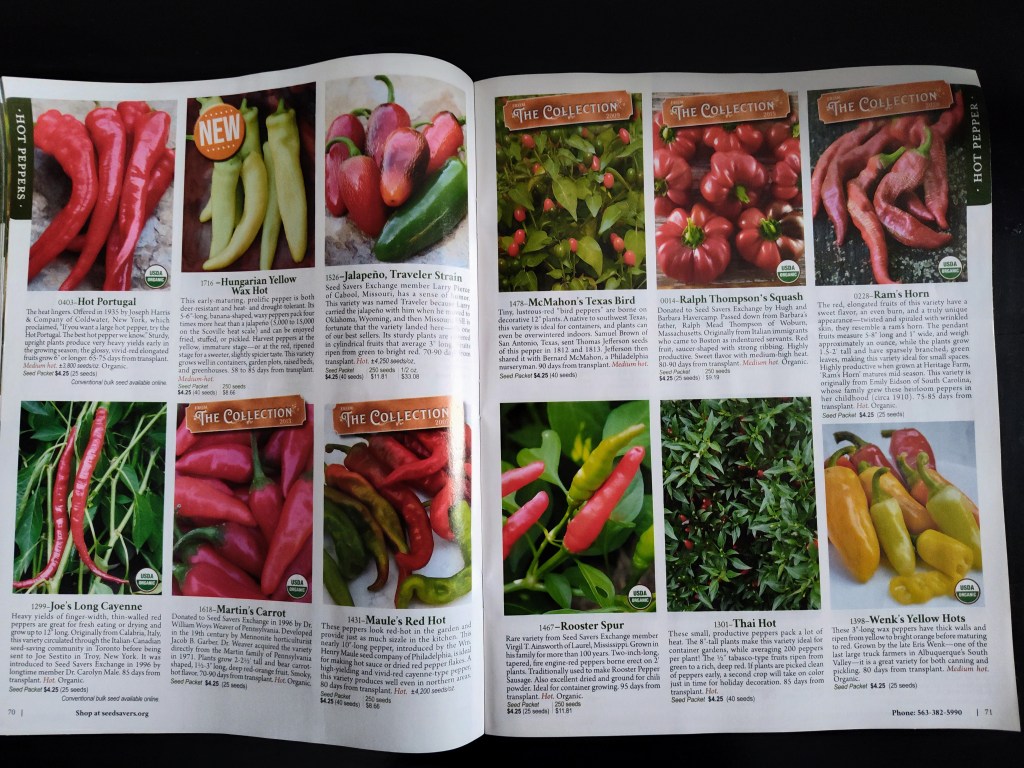

- Images – 1 point if there is an image for every seed; 1/2 (.50) point if fewer.

- Non-Seed Offerings – 1 point for each category (fertilizers, seed-starting items, merchandise, weed control, pesticides, garden gear, etc.)

- How Is it Organized/Ordered? – 1 point if its order is a positive; minus-1 point if it’s a negative.

- Beauty – This is completely subjective, but it’s my way of determining if it’s aesthetically pleasing to look at. Does it include original artwork? Are the images crisp and clean? Is the text easy to read? A maximum of 10 points can be awarded.

- What Sets it Apart or Makes it Unique? – This is another subjective category. What about a catalog makes it stand out from the others? A maximum of 10 points can be awarded.

Without further ado, here are the scores for the catalogs:

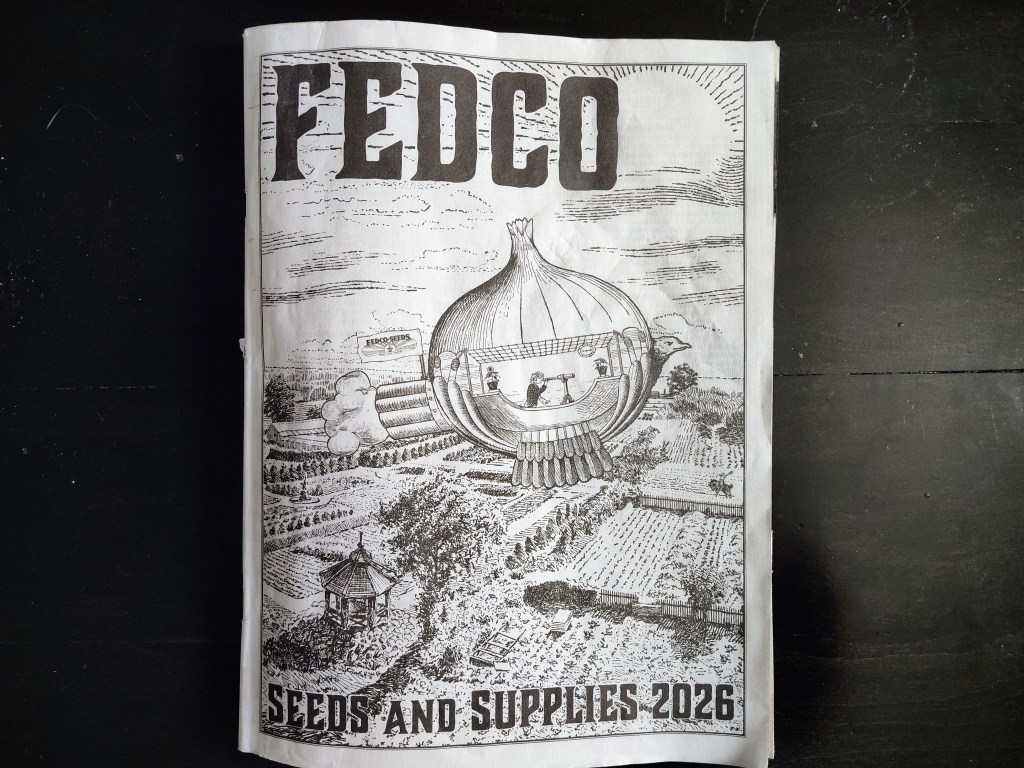

- Fedco – 543.25 Points

- Baker Creek – 451.25 Points

- Territorial – 417 Points

- Pinetree Gardens – 410 Points

- High Mowing Organic Seeds – 303.5 Points

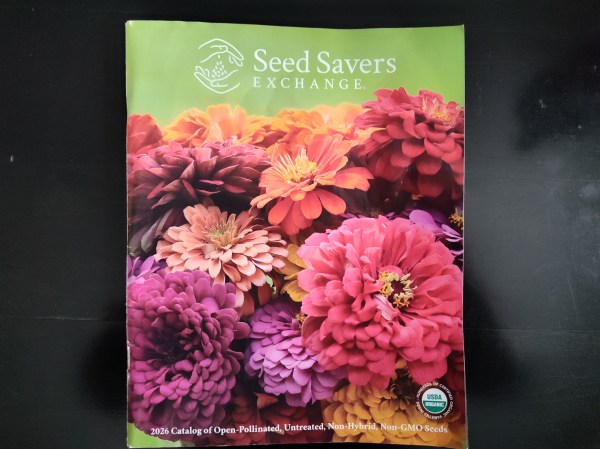

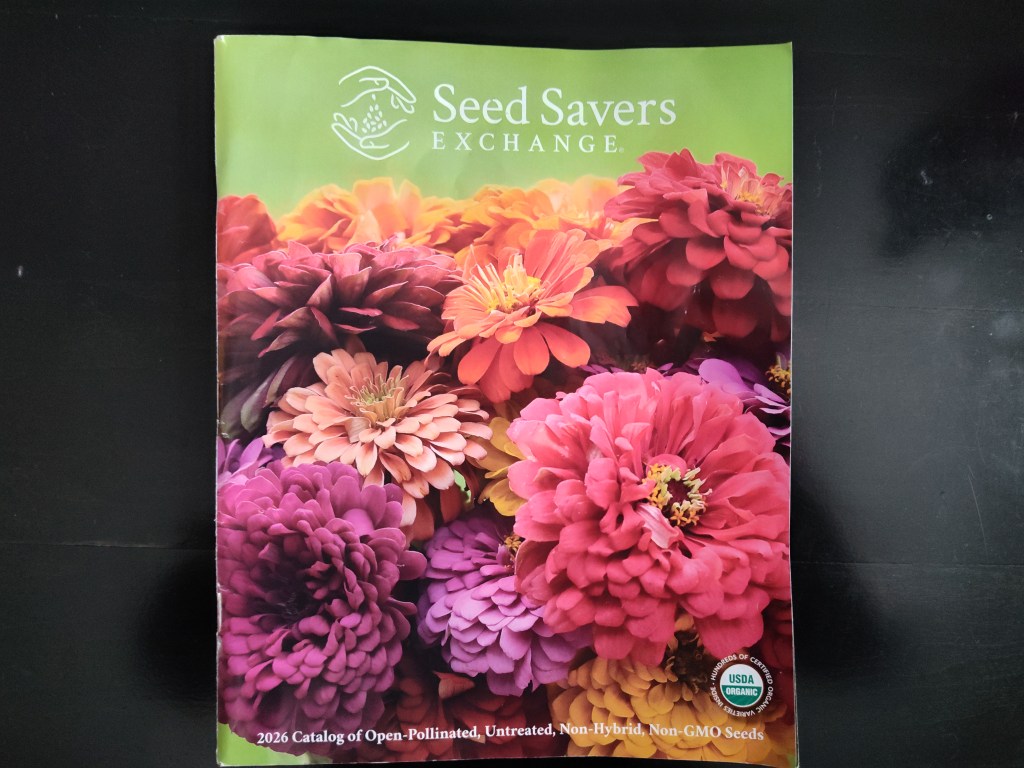

- Seed Savers Exchange – 247.75 Points

- Southern Exposure Seed Exchange – 238.5 Points

- NE Seed – 221.5 Points

- Sow True – 193 Points

Do the Scores Match My Subjective Opinions of the Catalogs?

The short answer is no. When I was putting these reviews together, I looked at each catalog and wrote the review individually, so I didn’t pay attention to the scores and how they compared to each other. Solely based on my subjective views, my order would be:

- Sow True

- Southern Exposure

- Pinetree Gardens

- Fedco

- Seed Savers Exchange

- Baker Creek

- High Mowing Organic Seeds

- Territorial

- NE Seed

The biggest surprise here is that the lowest-scoring catalog, Sow True, is actually my favorite. I love the design and shape of their catalog even though it’s on the smaller side. Territorial’s catalog, which scored high, was one of my least favorite catalogs, although the 5-8 catalogs on my subjective list are pretty close together.

I think the reason for this discrepancy is that my scoring system placed a lot of weight on the number of pages in each catalog, with one point being awarded for each page over 100. The reason for that was to award seed companies for offering thick catalogs that go above and beyond. I still think it was smart to award the catalogs for how many pages, but perhaps points should have been given on a tiered basis (1 point for 100-110 pages, 2 points for 111-120, 3 points for 121-130, etc.) Another scoring system would have been to award one point for every 5 pages above 100.

Another reason is that my scoring system intentionally awarded the objective traits, such as the number of seeds being offered, new seed varieties, and non-seed offerings. This naturally rewards the larger companies that can offer more seeds than the smaller companies. I wanted to reduce the likelihood that my personal thoughts and feelings could unfairly create imbalance in the scoring system. That was successful, but I think I went too far in the opposite direction, and some of the most beautiful catalogs didn’t rank highly. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter, because I can still follow up with my personal rankings, but I will adjust the scoring system for next year in an attempt to be more fair.

What Did I Learn?

I learned that I love catalogs from the companies that go beyond simply selling seeds. As a gardener, you can buy seeds almost anywhere in the spring. Go to any box store, home improvement store, or Agway, and you’ll find seeds. But not all seeds and seed companies are created the same. Some seed companies are businesses and operate with the goal of turning a profit. Others care more about educating gardeners and building a sustainable future than making money. You can perceive that difference in the companies’ catalogs. I prefer the catalogs that offer more than seeds. They’ll tell stories and teach lessons. I want to buy from companies that give back and support small farmers.

I know that I learned a lot by reviewing the seed catalogs. It forced me to slow down and really pay attention to what I was seeing and reading. Now, we begin the process of selecting the seed varieties that we want to buy, and I’ll be curious to know if we buy the bulk of our seeds from the highest-scoring catalogs (subjective or objective) or if they’ll be evenly divided. I’ll follow up with a post on what seeds we order. Thank you for reading.